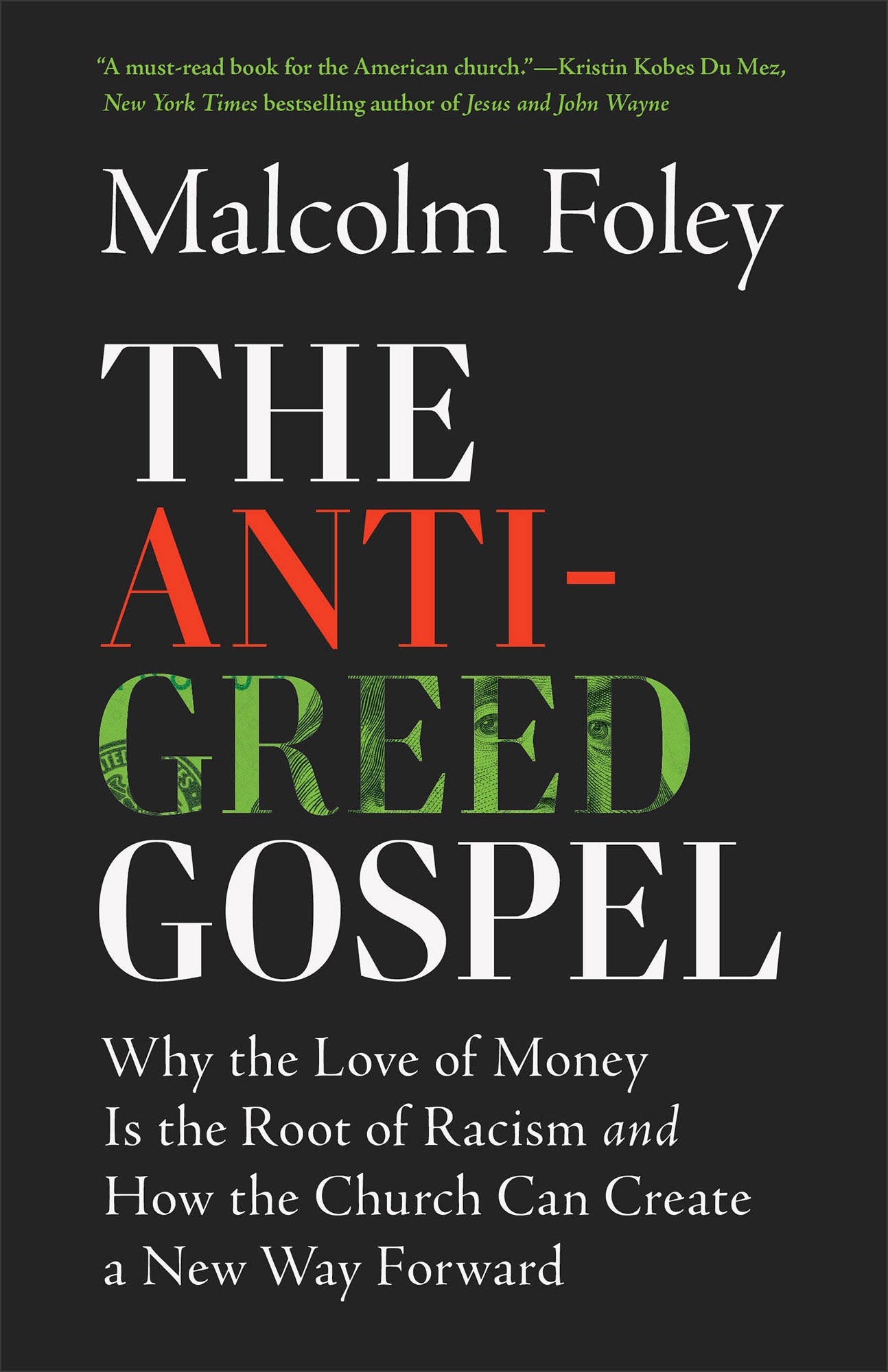

The Anti-Greed Gospel: Why the Love of Money Is the Root of Racism and How the Church Can Create a New Way Forward by Malcolm Foley (Brazos Press, 2025).

Every once in a while I come across a book that changes the way I look at the world. Dorothy L. Sayers’s The Man Born to Be King was one such book (though technically a play cycle rather than a conventional book). So too were Makoto Fujimura’s Culture Care, and Sandra Glahn’s Nobody’s Mother, and Elena Ferrante’s My Brilliant Friend. Each of these led to a fundamental shift in my thinking about a particular topic—faith, or history, or even my own family background—or about life in general.

Malcolm Foley’s The Anti-Greed Gospel is another such book. Foley, a pastor, historian, and advisor to the president of Baylor University, makes a provocative and convincing case for shifting our thinking on racism and how to overcome it. “Contrary to popular opinion,” he writes, “race is not primarily about skin color but about people seeking to categorize one another in order to exploit them. It is about greed.”

Foley backs up this contention with an abundance of historical evidence and scriptural insight. The tragic history of racism, he demonstrates, can be traced directly to the lust for wealth. White Europeans and Americans kidnapped and enslaved Blacks from Africa not because they hated them, but because they wanted free labor to help them accumulate money, land, and power. That is how the sin of racism took root, and that is why, Foley argues, efforts to eradicate racial hatred will never succeed unless they take greed into account.

After all, he shows us, greed continued to motivate racial persecution in the post-slavery era. We need only look at the horrifying practice of lynching from Reconstruction onward to see the pattern. Foley extensively cites the crusading journalist Ida B. Wells to show how flimsy or outright fabricated excuses for lynchings often covered up the real reason: the desire to hoard wealth and property and keep Black people from accessing them.

As Foley explains:

One of our primary questions whenever we encounter racism in the world is this: Who stands to benefit politically or economically from racist actions? We will find that when people act out of hate, such hate does not emerge from a vacuum. Somewhere along the line, self-interest crawled into the brain of the offender. After festering, it took a new form: hate.

Foley draws on Christ’s teachings about greed to drive his point home. “This book is precipitated,” he writes,” by the fact that rival gods require blood sacrifice. Mammon is no different. Jesus is not exaggerating when he says we cannot serve two masters: God and Mammon. … We will hate one and love the other.”

As I said, Foley’s powerful presentation of his case has altered my views on the nature of the problem. In the second half of the book, where he lays out potential solutions, he lost me a little, mainly because he is a committed pacifist and I am not. He spends a good deal of time promoting the idea, and I respect the thoroughness of his research and the strength of his convictions—especially as he’s arguing against his own self-interest—but in the end I still believe there’s a place for self-defense (and so did Foley’s heroine Ida B. Wells, as he acknowledges).

So I may not be Foley’s ideal reader, but I still deeply appreciate the overall moral vision he offers in this book, one that calls for Christians to demonstrate a love radical enough to push back against our culture’s profane worship of wealth and its deadly consequences. This battle is fought, he shows us, on both the spiritual and material levels, and fighting it will require our imagination, our creativity, our honesty, and our willingness to walk alongside the oppressed and the suffering. If I can’t agree with Foley on every strategic detail, I’m still very grateful for the wisdom and guidance he offers here. Books that change your thinking don’t come along every day; when they do, they should be savored.

(Cover image copyright Brazos Press. Thanks to NetGalley for the advance review copy.)

Book Links:

The Anti-Greed Gospel on Amazon

The Anti-Greed Gospel on Bookshop

(Note: As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualified purchases.)

Good engagement!

In his quirky 1908 novel “The Man Who Was Thursday”, during a conversation, one of GK Chesterton's characters paints the rich as being anarchists:

“You’ve got that eternal idiotic idea that if anarchy came it would come from the poor. Why should it? The poor have been rebels, but they have never been anarchists; they have more interest than anyone else in there being some decent government. The poor man really has a stake in the country. The rich man hasn’t; he can go away to New Guinea in a yacht. The poor have sometimes objected to being governed badly; the rich have always objected to being governed at all. Aristocrats were always anarchists, as you can see from the barons’ wars.”

“As a lecture on English history for the little ones,” said Syme [another character], “this is all very nice; but I have not yet grasped its application.”

“Its application is,” said his informant, “that most of old Sunday’s right-hand men are South African and American millionaires. That is why he has got hold of all the communications….”

1908!

I agree. It's a terrific book.