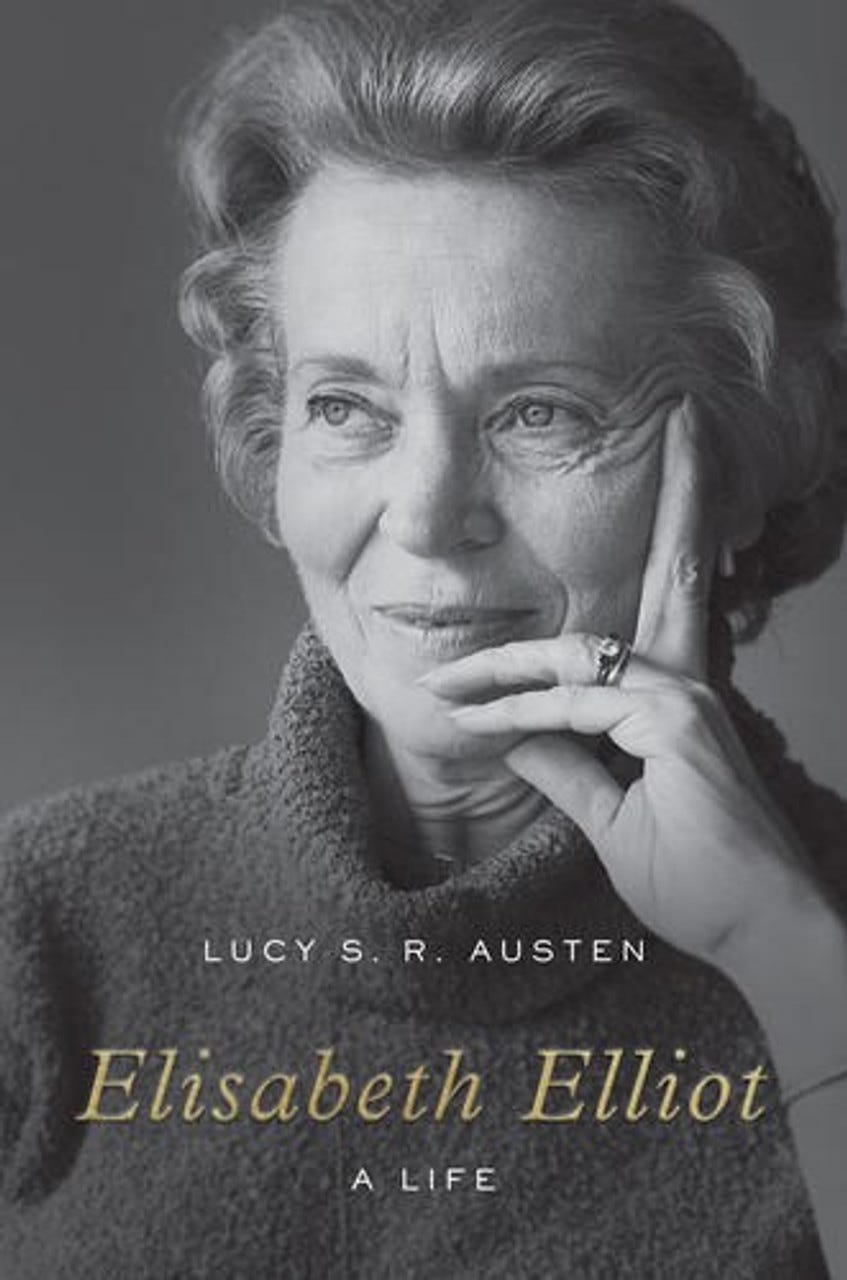

Elisabeth Elliot: A Life by Lucy S. R. Austen (Crossway, 2023).

When I was growing up, the name Elisabeth Elliot meant one thing to me: Passion and Purity, her 1984 book that helped shape the views of an evangelical generation on love, sex, and marriage. It was a very long time before I could hear her name without mentally wincing.

Elliot’s life and career, in fact, were a strange mixture of striving to live authentically for God, and advocating standards that she herself had found impossible to live up to. I still believe that, with the best intentions in the world, she did damage with that book. And yet, to read about her life with all its struggles and accomplishments is to find oneself respecting her strength, commitment, and courage, and wishing that some things could have been different.

I first had this experience when Ellen Vaughn, an old friend of mine, published Becoming Elisabeth Elliot, the first part of her two-volume biography (with part two due out this fall). Now Lucy S. R. Austen has released a massive new biography that fleshes out the picture even further.

The scope of Austen’s achievement here is mind-boggling. In 525 pages, she gives the full sweep of this woman’s very active life while simultaneously drilling down to the smallest details. The length of her book may appear daunting, but Austen tells the story so compellingly that I couldn’t stop turning pages. She was given only limited access to Elliot’s journals, but what she did with that access is truly impressive (one can only imagine what she could have managed with full and free access!).

What you already know about Elliot probably largely depends on your demographic and (if you have one) your denomination. Long before she made her indelible impression on my generation, Elisabeth Elliot, née Howard, was a zealous young missionary with a dream of translating the Bible into new languages for previously unreached people. She also dreamed of marrying fellow missionary Jim Elliot. The two had fallen in love in college, but Jim had been “blowing hot and cold,” as Austen puts it, for some time, asserting that God had not yet given him permission to marry. It was this flawed and often frustrating relationship that Elisabeth would try to turn into a romantic template in Passion and Purity, unwittingly screwing up Gen X’ers everywhere.

Jim and Elisabeth did finally marry and have a daughter while working in Ecuador. But their time together was cut tragically short when Jim and four fellow missionaries were killed by members of the Waorani tribe. Elisabeth would go on reaching out to the tribe and even spend a couple of years living and working with them, earning worldwide attention, before returning to the United States.

I found the middle section of the book, covering the 13 years after Jim’s death, the most poignant, with its depiction of Elliot’s growth and the increasing complexity of her thinking. Still holding strongly to her faith, she was letting go of a lot of misguided assumptions and simplistic ideas that had once gone with it. From her time among the Waorani as well as her new experiences mingling with publishers and artists, she had learned how to live with others without forcing her ideas and way of living on them. She was intentionally moving outside her evangelical bubble, recognizing and discarding her own prejudices, and becoming increasingly thoughtful, well-read, and creative.

What, I kept wondering, had happened to this Elisabeth Elliot?

The answer is closely bound up with those views on men, women, and marriage that would eventually find their way into Passion and Purity. Elliot would marry twice more, and each time, her ideas on wifely submission would lead her to squeeze herself into the mold she thought marriage required—sometimes to the detriment of the marriage itself, and always to the detriment of that more open attitude she had once cultivated. Both times she picked husbands with hidebound views and domineering tendencies, aggravating the problem.

It was news to me, and probably will be to many, that Elliot’s second husband, Addison Leitch, apparently started pursuing her while his first wife was dying of cancer. That should have been a giant red flag, but Elliot was very tired of having to be a strong single woman, and in this case was ready to decide for herself what God’s will must be. As Austen astutely observes at one point in the book, “Perhaps [Elliot and her brother Thomas Howard] shared the same blind spot, the tendency to leap from ‘this is the way things are’ to ‘this is the way things ought to be.’”

Specifically with regard to Leitch, when he started officially taking her out about two weeks after his wife’s death, this philosophy, Austen suggests, seems to have led her to think, “God must have directed her in the path that led to their meeting; God would not lead her into temptation; therefore there could be nothing wrong in the relationship.”

At all stages of Elliot’s life and career, Austen offers this kind of clear-eyed, objective commentary on her subject. Her free exploration of the good, the bad, and the ugly is a gift to anyone who wants to better understand the thinking, not just of Elliot, but of her generation and her culture—and perhaps something about our own.

It’s clear from Austen’s telling that the faith that shaped and drove Elliot was real and substantial. It was Elliot’s very human weakness not to realize that other forces were shaping and driving her as well. During her college years, for instance, we see a young Betty Howard who wrote reams of purple prose about her earnest desire for God to search out and eliminate every vestige of sin in her life, and who also casually dropped horrible racial slurs in letters to her family without a second thought.

As I wrote earlier, that kind of prejudice was something she eventually learned to recognize and deplore in herself. But for much of her life, in one way or another, she would display these sorts of perilous blind spots. (Viewers of the Amazon Prime documentary Shiny Happy People—or anyone who’s been following recent developments in evangelical Christianity, really—will be jarred by her late-in-life speaking engagements with Bill Gothard’s organization.) To see these in her is to feel sobered and humbled about what nastiness might be lurking in our own minds and hearts that we haven’t yet spotted.

For many reasons, Elisabeth Elliot’s story is key to understanding evangelical faith in 20th-century America and beyond. With her wise, levelheaded approach, her rational voice in dialogue with Elliot’s often fervid one, Austen proves herself an ideal person to tell that story.

(Cover image copyright Crossway. Thanks to Crossway for the advance review copy of this book. All quotations checked in the published version.)

Book Links:

Elisabeth Elliot: A Life on Amazon

Elisabeth Elliot: A Life on Bookshop

Other Links:

At Dickensblog, I reviewed Charles Dickens and Georgina Hogarth: A curious and enduring relationship by Christine Skelton.

Gina -

You wrote a spot on review of this amazing book. Eliott was a huge influence on me during my years of the early 80’s at Wheaton as a young highly impressionable new evangelical. As I matured - I was troubled with many of her strident ideas and opinions that she often passed off as “gospel essential”. But I found Lucy Austen’s bio a rich and wonderful read of a complex women who I continue to deeply admire - albeit with some very differing views than Elizabeth. What strikes me is her steady and ever growing awareness of her ever faithful God and His keeping care.

I grew up in the 1950s and 60s in Fundamentalist churches. We were familiar with Elisabeth Elliot and her story. I'm glad that Lucy Austen has provided a nuanced, balanced look at a complex person. I didn't know that she had appeared in her later years with Bill Gothard. My parents followed the Basic Youth Conflicts program he wrote, which caused unbridgeable estrangements within our family. I admire Elisabeth Elliot as someone who followed what she believed, but don't subscribe to her religious views