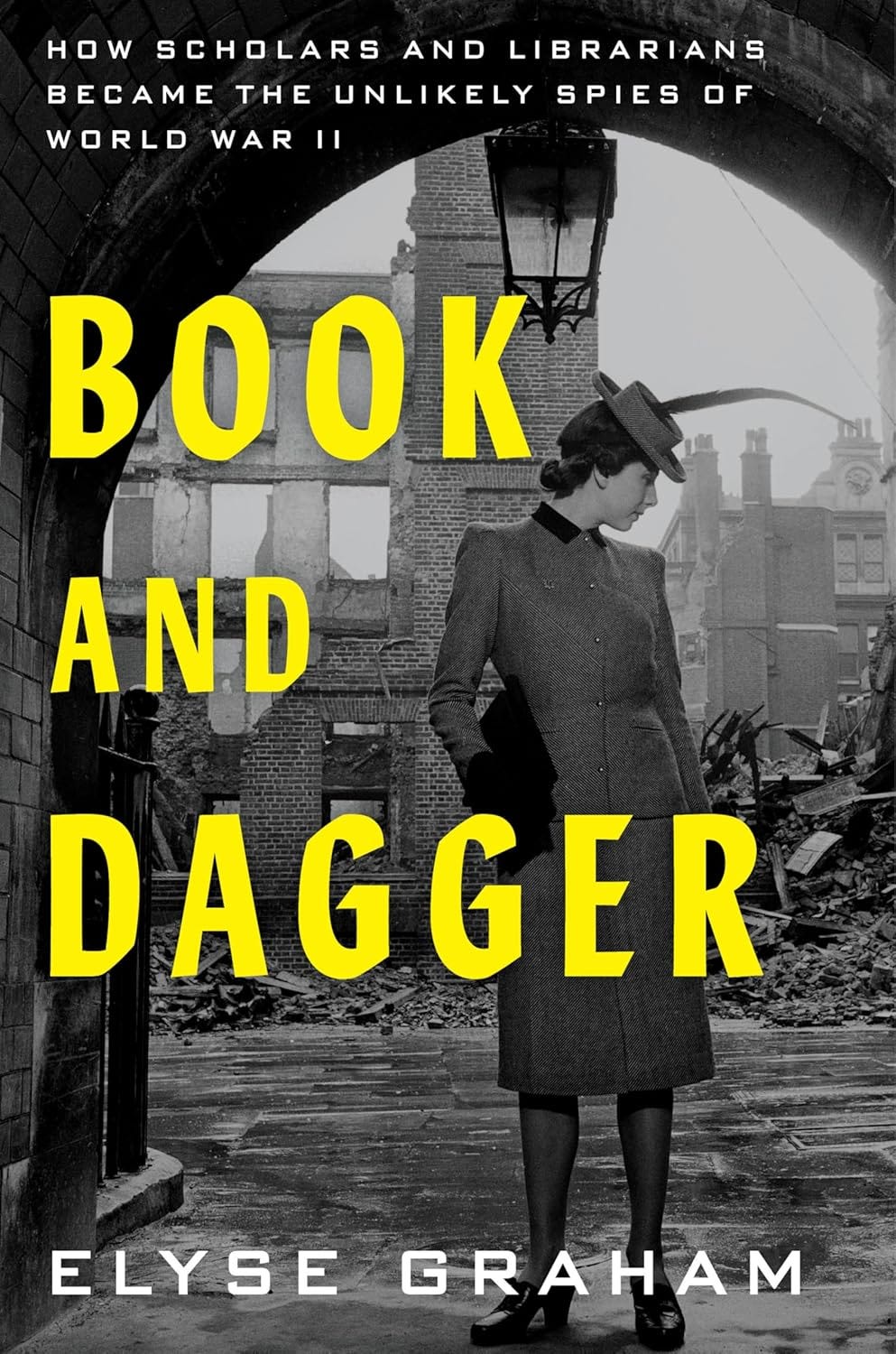

Book and Dagger: How Scholars and Librarians Became the Unlikely Spies of World War II by Elyse Graham (Ecco, 2024).

“The story that follows is not going to sound like it really happened, but it did,” historian and professor Elyse Graham assures us at the beginning of her new book. As its subtitle spells out, Book and Dagger: How Scholars and Librarians Became the Unlikely Spies of World War II traces the stories of “bookish types” who were recruited into American intelligence during World War II.

In this lively narrative, Graham explains that the U.S. intelligence service was very much a fledging operation at the beginning of the war, needing to hire a lot of people and quickly invent new ways to get things done. But those in charge knew enough to realize that the humanities—everyone from researchers to professors to artists to actors—would have to play a key role. More experienced agents and military members knew how to gather information; scholars and librarians knew where to look for it and how to read it. Though these unconventional recruits would undergo regular spy training, learning to attack and defend and all the rest of it, their real value was in their analytical skills and, in many cases, their creativity.

Graham puts readers squarely in the middle of the action, inviting us to identify with her scholarly subjects and try to feel what they must have felt as they moved into a field more uncertain and dangerous than they had ever known. She supplements the historical record with speculation and scenarios that are vividly imagined, though grounded in reality: What happened when a literature professor was asked to kill a double agent? Did he actually slide his knife into the other man when they encountered each other on the street? Could you?

But the bulk of the story is devoted to the unique gifts these agents brought with them to their new craft, and the ways they put them to use. “Paper was a weapon” to them, Graham writes, whether it came from scientific journals or newspapers or maps or phone books or any other of dozens of different sources, expected and unexpected. The story of how they wielded it is fascinating and at times downright entertaining, though Graham never loses sight of the stakes (descriptions of the gruesome killings of a couple of these agents is enough to firmly fix these in our minds early on). She brings extensive research, imagination, and wit to her telling of the tale, along with a keen understanding of human nature.

“If [an agent] wants to know something specific, but doesn’t want people to notice her asking questions, she should simply make incorrect statements while in the company of experts,” she writes wryly at one point. “Her companions will correct her, especially if they’re men.”

Above all, Graham shows a firm grasp of the underlying value of the humanities and the kinds of people who are drawn to them, not just during wartime, but in every effort to strengthen a nation and a world. Immigrants and refugees, women and men, Jews and Gentiles all brought crucial perspectives, capabilities, and values to the task of winning the war and then helping to establish the peace. As she puts it:

Hitler’s impression of America’s weaknesses started with the fact that it was a nation filled with what he saw as lesser races. Hitler also despised intellectuals, regarding any career that entailed digging through libraries as particularly pointless. But that type of thinking was why the very people Hitler’s Reich sought to exclude or destroy were singularly equipped to defeat him.

I’ve rarely seen a better or more important example of the ostensibly weak putting to shame the mighty. It’s an example that will and should stay with us.

(Cover image copyright Ecco.)

Book Links:

Book and Dagger on Amazon

Book and Dagger on Bookshop

(Note: As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualified purchases.)

Goodreads Links:

The Sequel by Jean Hanff Korelitz

There are numerous books, fiction and non fiction, written about the ways in which Britain fought Hitler that were intellectual and not the usual military approach. An American perspective would be interesting to read. I wonder did this new strategy start before the US joined the fight or before? I find these details fascinating. Thank you.