An engrossing theological novel is a rare thing, but that’s what

has given us with her book Broken Bonds: A Novel of the Reformation. The story focuses on three great religious thinkers and leaders of the time: the reformers Martin Luther and Philip Melanchthon, and the scholar and theologian Desiderius Erasmus, who opposed their project. We see them struggle with each other and with their own fears and doubts as they remake the spiritual and intellectual landscape of 16th-century Europe, in a tale that shifts seamlessly between the epic and the deeply personal. Amy kindly took the time to answer a few questions from me about her book.Q: I was struck by how well and how fully you assumed each of the three main characters' viewpoints, even though they're all so different, so that we can see and sympathize with each man's beliefs and values, and understand why their relationships with each other are so fraught. How difficult was that to do, especially when each one was so sincere and so convinced that he had the right interpretation?

A: One of the most important traits a novelist can have is empathy: the ability to put yourself in someone else’s shoes, imagine things from their perspective, and have compassion on them. Without empathy, novelists end up essentially writing stories about themselves, which is certainly what we see all too often. My policy for this story was that whichever character’s perspective I was writing at any given time, I was 100% on their side. Of course, there were times when I disagreed with one or the other of them, but I tried to think of how I could put their views in the best possible light: what would be most convincing to me personally.

As an example, during the period when this story is set, Martin Luther begins disagreeing quite strongly with other Protestant Reformers over their understandings of the Lord’s Supper. It was a bit mystifying for me at first why Luther should choose that particular hill to die on: why the metaphysics of what happens in the Lord’s Supper is an issue worth splitting the Church over. What’s the big deal if you aren’t literally consuming Christ’s body and blood? Then this thing just came into my mind: it’s like Christ is holding back, unwilling to really give himself to us, if there isn’t a real presence in the Lord’s Supper. So, in the novel, Luther says something like that.

But I do find it is very true when two people get into a dispute that neither one is 100% right or 100% wrong. They are each heavily affected by their personal context, which determines their point of view. It’s a kind of tragedy when people split over issues where they really could have had some accord, and I tried to show that in the book.

Q: Do you think that perhaps in another age, when communication was much easier and more rapid, the three men might have understood each other better? Or might that have made their relationships and their conflict even more difficult?

A: I do sometimes wonder how they would have fared in the age of Twitter, or whatever Twitter is giving way to now. Erasmus was such a master of the long-form letter, I have a feeling he would have stuck to e-mail, though he would have been a lurker on social media. (He always wanted to know the latest gossip!)

Melanchthon would have likely been one of those people who only links his own works or shares famous quotes on social media. We all assume Luther would have been an avid poster of a polemical nature. After all, the “Luther Insulter” account has a lot of followers! Would he have gotten himself cancelled? Well, he got the 16th-century version of a cancellation when he was excommunicated. Perhaps it is better that we never know what he might have said.

But I have a feeling that new methods of communication would have done little to help their relationships. We certainly have seen in our present day that knowing more of what people are thinking tends to make it more difficult to stay friends, not less. Then again, I have so many friends who I have connected with through digital communication, so who’s to say?

Q: How closely did you stick to what we know about the personalities of these characters? Did you take any license there, and if so, why?

A: On the one hand, I am very upfront that what I have created are three characters who bear a strong resemblance to the historic Luther, Erasmus, and Melanchthon. On the other hand, I do strive for historical accuracy in everything I do. There is a spectrum among historical fiction authors. Some stick rigidly to the established facts, while others only allow the facts to occasionally interfere with their personal creation.

My goal is to never contradict the historical record, but to create a fully fleshed out narrative, it is necessary to focus on some events and not others, add secondary characters and subplots, and form an arc for each character. Before I began writing, I asked myself, “What is the major issue at play for each character?” And specifically for this tale, I asked, “What is each character afraid of most?”

I also favored plot lines that would help to hold the three storylines together, since the main characters rarely share scenes together. Overall, minimal license was taken, and such changes as were made I think were inevitable in transferring to the medium of a novel.

Q: For me, the book often had the feel of movies like Becket and A Man for All Seasons, where momentous events turn upon fine theological points, and religious debates have life-and-death stakes. Did any works like these inspire you as you were writing?

A: I do love historical films, and I have an almost cinematic mindset when writing scenes. It is difficult enough to write a novel that focuses on a theological debate. A film is even more difficult! You must find ways as an author to make the real-life consequences of those debates painfully clear.

One trap that filmmakers always seek to avoid is having too many scenes with people just sitting around and talking. This is also a challenge for the novelist, although perhaps to a lesser degree since you do not have the visual element. Fortunately, the theological debates of the 1520s had very clear personal and political ramifications, so my task was to keep those constantly in the reader’s mind, and when possible, to show the effects as they play out.

The advantage of a novel is that you can hear the characters’ inner monologues in a way that is rarely true for films. In both Becket and A Man for All Seasons, the heroes can come off as sanctimonious at times. However, an internal monologue helps us to see characters’ fears and failings—their vulnerabilities. We are more likely to identify with them this way.

While there was not one particular film I consciously took as inspiration, I did realize after completing the book that the Luther/Erasmus debate bears a kind of similarity to the Mozart/Salieri rivalry in Amadeus: an older man who has the respect of the establishment clashing with an upstart young genius with novel ideas. I do love that film, and it may have inspired me subconsciously. (Luther and Mozart were also two of history’s greatest scatological jokers!)

Q: We get very familiar with Luther's digestive ailments and Erasmus's kidney stones! Why was it important to you to go into detail about these men's physical suffering, along with all the spiritual and emotional strain they underwent?

A: It can be difficult to find commonality with historical figures that far back, because the way they conceived of the universe and the narratives that guided their reasoning were so different. It really is a work of translation attempting to put the modern reader in their shoes. One way this can be accomplished is by focusing on things felt in the body, because while modern medicine helps us in certain ways, a headache still feels roughly the same as it did in 1524.

However, the themes of the book also influenced my choice to focus on the physical. Luther’s theology is notable for its positive view of the physical world. “Earthy” is a word often used to describe it.

Additionally, the working title of this project was Fear and Trembling, and I wanted to explore the different sorts of things people fear, how fear affects them, and how it can be overcome. I have experienced periods of intense anxiety in my life, and what I have learned is that fear is a physical experience as much as anything else. It can sometimes be difficult to determine if the mind is causing the body to act this way, or the body is causing the mind to have dark thoughts.

Finally, a good novelist is supposed to “show, not tell,” so it is often good to explain how a person is feeling physically rather than having them say, “I’m scared!”

Q: Each of the three men is trying, as far as he's able, to keep the religious conflict civil and on an intellectual level, but all around them are people who keep taking it to violent extremes. Do you think that, if not for the violence causing so much pressure and fear, their relationships might have been different?

A: Possibly. The period when this story is set, 1524-25, is when the Reformation started to cause more widespread civil unrest and ultimately a lot of bloodshed. When Luther first posted his Ninety-Five Theses in 1517, he attracted fans from all sectors of Western Christendom. Whatever issues these individuals had with the Church, they imagined that those (and only those) were the issues that Luther was protesting. Even Erasmus had good things to say about Luther early on.

Then over the next decade or so, we see a gradual loss of former supporters. When Luther turns decisively against the papacy in 1520, a big group deserts him. One of the next desertions occurs in the mid-1520s as it moves from a theological debate to a political one. People begin to feel that society is falling apart. They see increasingly radical preachers calling for violent uprisings. Luther condemns these preachers, but there is a sense that is it all his fault. He opened Pandora’s Box, and now everything bad is getting out. And remember, most people don’t understand the theological nuances of what Luther is arguing. They just look at the uptick in violence and say, “If this is the fruit, the tree must be rotten.” There is no chance at that point that Erasmus will ever be friends with Luther, because promoting peace and ending war is central to Erasmus’ whole project. Even Philip Melanchthon has his doubts about Luther during the height of the German Peasants’ War of 1525, though they were able to patch things up.

Q: You movingly portray Philip Melanchthon's feelings of being torn between Luther and Erasmus, both of whom he considers his friends even though they're so different and oppose each other so fiercely. How do you think these opposing forces influenced and shaped his own character ?

A: Melanchthon’s love of Erasmus speaks to his passion for educational reform, as well as the recovery of wisdom from the ancient Greeks and Romans. Erasmus is tied up with Melanchthon’s past. The famed Hebrew scholar Johannes Reuchlin, a great-uncle and surrogate father of Philip Melanchthon, was good friends with Erasmus.

On the other hand, Melanchthon is tied to Luther through his genuine passion for the gospel and Church reform. His decision to join Luther’s reforming crusade causes him to lose the love of Reuchlin, who then dies soon afterward. In some ways, that leaves Erasmus as a living reminder of Reuchlin and a path of scholarship that Melanchthon could have taken: he could have remained entirely on the secular side of academia and lived a comparatively comfortable life. Instead, Luther convinces him to move over to the sacred side, teaching and writing theology.

Melanchthon loves both Erasmus and Luther in their own ways, but he shares different things with each of them. At various times, he seems to be more under the influence of one or the other, and when they end up debating in public, it causes a lot of angst for Melanchthon. So, there are deep wounds in his person that get reaggravated by this skirmish, and that helps to solidify Melanchthon’s purpose going forward. He will end up carving out a niche for himself as a diplomat, educational reformer, and instructor of a generation of Lutheran pastors. He will not write as many polemics as Luther, though he is willing to do so on occasion, as with the Apology for the Augsburg Confession. But I think Melanchthon began following Luther like a young person in love, rushing headlong, heedless of the potential risks. Going forward, he is a bit more cautious and calculating.

Q: I understand you have a sequel to Broken Bonds coming soon! What can you tell us about it?

A: There certainly is a sequel! It is called Face to Face, and it picks up right where Broken Bonds leaves off. It will be released on November 11 this year, and it describes the events of 1525 leading up to the publication of Luther’s response to Erasmus, The Bondage of the Will. So, you can learn some of the basics about the plot by simply consulting the history of that year! However, there will also be a few surprises in store. I am excited to get this part of the story out there. It is part thriller, part war drama, part romance, part dark comedy. A little something for everyone!

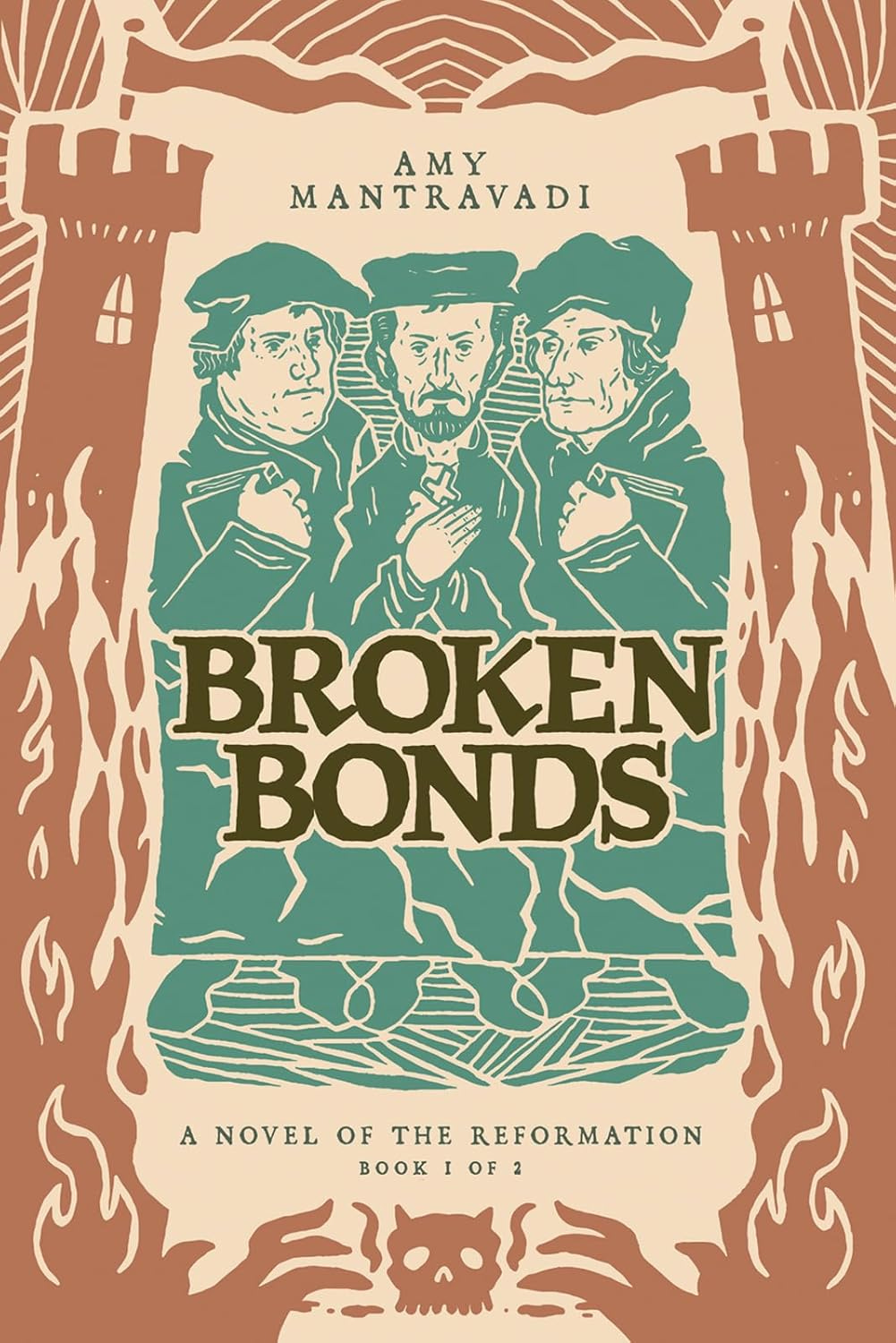

(Cover image copyright 1517 Publishing.)

Book Links:

Broken Bonds on Amazon

Broken Bonds on Bookshop

You might do likewise fictionally? Dorothy and Jack. Throw in a bomb, Flannery O’Connor!